COUNTRY LIFE

Talking about his past is hard, as hard as finding the house he shares with wife Katty and little Eddy, 10. We’re in East Flanders, close to Eeklo, where he was born. Reaching him was something of a performance. I’d to take two trains and a bus from Brugge, where I was staying, little more than 30km away. Equally difficult was having him share the memories of the years during which he built his legend…

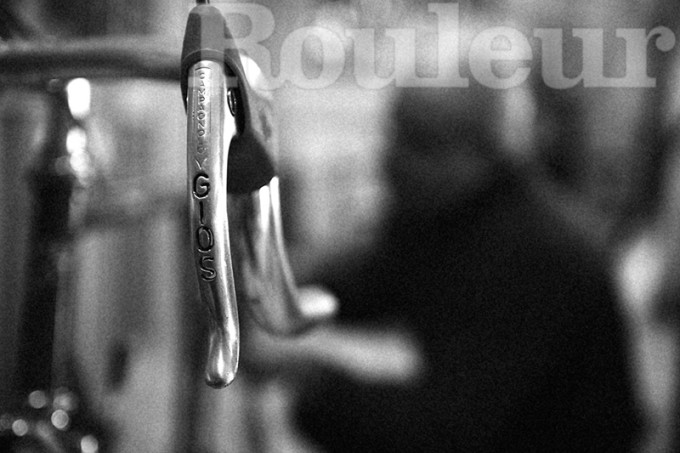

It becomes apparent from the first question; “What do you remember of the first Roubaix you won with Brooklyn?” His reply is “not much”, followed by a series of insistent questions about Aldo Gios, about his old DS, about whether Perfetti is still in Milan. I understand immediately that his sporting career happened a very long time ago, in every sense. His answers are short and concise and entirely Flemish, at variance with these oppressive summer temperatures. He offers me water and coffee as we settle in the shade of a tree.

Do you still have a relationship with the cycling world?

I’m fed up with cycling. Sometimes they invite me, but as often as not I watch it on TV. The races are too tactical, particularly in stage races, and the stages are always the same. There’s always a break in the opening kilometres, and nothing happens until 20km from the finish. They bunch does nothing until then, and you already know who is going to win. I turn the TV on to watch the sprints; I like them and I always watch them. In 2003 I was in Zimbabwe, thanks to a TV production company. I was there to try to develop cycling, and to train some kids. We created a ‘cross course, and the best amongst the riders came over here to train. Some of them are still here today. It was an interesting experience; I like a challenge…

What’s the difference between cycling today and during your career?

I think the intensity of the training has changed a lot. When I was riding it was much tougher. We would ride a 260km stage with seven climbs, whereas today that would do that over two days. We didn’t have all these rest days, and there were no compact chainsets. We had 53/41 with a seven speed block, whereas today they have eleven. And then of course there’s the money. Merckx’ son, Axel, earned more than his dad during his career, though he barely won. I guess money conditions things a lot, like in all walks of life.

How much influence has the increased technology applied in training had on performance?

Not much. Today’s bikes are good for speeds of 45-50kmh, but ultimately it’s the legs which push the pedals. In the seventies we too did a 48-49 average speed, with toe-clips, woolen jerseys and all that stuff…

They nicknamed you Mr. Roubaix. How do you win such a hard race four times?

Paris – Roubaix never worried me, it was a lot like ‘cross. Races like Tirreno-Adriatico were harder, notwithstanding the fact that I won it six times I found it much more difficult. No other Belgian has won it; Boonen and Gilbert some stages, but nothing more…

Who amongst today’s riders is similar to you?

Nobody. We didn’t really do tactics. We rode to win and we didn’t leave even the small races to the others. These days they use races to train. We were more complete, capable of winning sprints, in the hills or against the watch.

You always won classics. Were you not well suited to stage racing?

That’s not true. I won Tirreno six times, the Tour de Suisse… I won more than ninety stages, many at the Giro, which was always the hardest stage race. At the Tour there were fewer climbs, and they weren’t as steep. In Italy it was different. Look at this years’ Giro. There were 38 genuine climbs, like we had in 1975, with gradients up to 18%. The problem with the Tour is the heat. There were days when it was insufferable.

Do you still have the Ferrari that Perfetti gave you for winning Milan – Sanremo?

No, I sold it a few months after. It cost a fortune, 4km for a litre of petrol. It wasn’t for me…

I’ve heard about when you left the hotel with the team car keys in your pocket, when they all had to come looking for you. Were you a serious athlete?

(Laughing) Yes, it’s true, though I was a serious athlete. If you’re not serious you can’t race till you’re 40 like I did, training hard, eating well, sleeping correctly. With these three rules you’ll go far and fast. However I was in my twenties and at that age you sometimes have to have some fun in your life, though not like the footballers of today who are always out and smoke. Smoking is a disgusting habit.

Of all the races you won, is there a particular memory?

The 1975 Tour de Suisse. I won six stages and was second four times. I won the GC and the points, ahead of Merckx.

How do you view your past? Does it leave you a little melancholic?

I don’t find it melancholic to look back. I had fun then and I have fun now.

What do you remember from the beginning of your career?

I started winning races here in Belgium, but the federation had no money. I therefore took the chance to go to ride in Italy, where I stayed a long time. The people there loved me, and I loved Italy. Sometimes I still see Moser, and from time to time he comes here to see me. Then I often go to Italy to see friends, to Lucca or Cesenatico…

You’ve a ten-year-old. Would you encourage him to ride?

I don’t know yet, it’s too early. We’ll speak about it when he’s 16 or 17, but for now he plays as striker for a local football team. I like following football.

Do you still ride?

Only when it’s warmer than 20º, in spring and summer, but these days I prefer jogging, 30km a week. I just have to stay in shape to run for 30 minutes, where with cycling you need to go out for two or three hours, with all that I have to do here…

How do you pass your days?

I go to bed at 10 o’clock and I get up at 5. I run or ride a little, then take my boy to school. At home I do the cooking, and then I work in the fields, the vegetable patch, with the animals. I’d say it’s the perfect country life.

Before taking my leave, I ask what he thinks of the nickname “the gypsey”. He shrugs his shoulders with apparent indifference.

Roger De Vlaeminck is one of those athletes who don’t live for what they did, for their memories. He’s left them in a drawer, to be opened only when it’s worth it, and above all he has found new stimuli and emotions in his daily life. He talks about his life as a cyclist with the serenity of a man of the country, without particular emphasis. Without the emphasis he could allow himself in view of his place in the history of cycling…

The discussion turns to politics, to football and to Italian food. He talks of Ronaldo and Messi, and when I ask him if he still has something from the bikes he rode he says he’s no use for them now. Rather he shows me, with some pride, the digger he uses in the garden. With a smile he says “this save my back these days, when I’m working the fields.”

His eyes light up when he talks of his animals and the fields he looks after day after day. He shows me his tomatoes, the aviary where he keeps his birds. He introduces me to Oskar, the blackbird only he may approach, to the deer he chose amongst hundreds of others because it was the least timid when they met. Finally I meet the dogs Bobby, Snoopy and Aiko, who escort us to the gate.

Roger De Vlaeminck left a deep impression. When my mother, who knows nothing of the sport, heard that I was to meet him she said “I know him, he rode during my times… he was strong”. To stay in the memory of the uninitiated means he was a genuine great.

Paolo Ciaberta